History of tapestries

During the Middle Ages, tapestries served a predominantly utilitarian purpose. Initially conceived to shield medieval rooms from dampness and cold, they adorned the stark walls of expansive castles, transforming vast spaces into more comfortable living quarters. The tapestries employed to embellish the grand stone castles were sizable, necessitating extensive looms, a considerable workforce, and substantial investments. Manufacturing hubs of this nature burgeoned in affluent towns, typically situated in weaving centers.

By the year 1500, Flanders, particularly Brussels and Bruges, had emerged as the primary production hubs for these intricate textiles. Owing to their grand scale and intricate craftsmanship, tapestries evolved beyond mere functional items; they became symbolic investments and expressions of wealth and power. In the early tapestries, individual figures or compact groups stood prominently against backgrounds, which were often either plain or adorned with botanical motifs or the renowned "mille fleurs" (thousand flowers) tapestries.

This artistic form gradually ascended to the status of one of the preeminent visual arts, standing alongside painting, sculpture, and architecture.

The evolution of tapestries witnessed a heightened level of intricacy, portraying elaborate battle scenes or expansive assemblies of figures organized in tiers beneath architectural marvels. Moving into the 16th century, patrons began to commission tapestries featuring their cherished pastimes: hunting, depictions of peasants engaged in work and leisure (often in disguises themselves). Subsequently, the vogue for "verdure" emerged, showcasing pastoral landscapes that frequently captured the essence of their estates.

This refined art form thrived on the patronage of affluent sponsors, with renowned manufacturers such as Beauvais, Arras, Gobelins, Aubusson, Felletin, Audenarde, Bruges, and Ghent flourishing in regions ruled by opulent kings and ecclesiastical monarchs. Naturally, the selection of subjects was determined by those commissioning the tapestries. Notably, all these esteemed manufacturers were situated in the northern regions of France and Flanders, encompassing the present-day Flemish part of Belgium.

In the 17th century, the inaugural royal tapestry factory, Les Gobelins, was established in Paris, becoming a hub where hundreds of tapestry artisans diligently worked during this era.

Artisans collaborated in groups, each meticulously painting and weaving their craft into the opulent and vibrant scenes showcased in this gallery. Throughout history, designers have wielded significant influence in the creation of truly exceptional tapestries. Take, for instance, Francois Boucher, who served as the designer for Beauvais since 1736. Over a span of 30 years, he crafted six tapestry sets, each comprising 4-9 pieces. A remarkable legacy, his designs birthed at least 400 tapestries, representing magnificent masterpieces of the rococo style.

As the 19th century drew to a close, wool and silk tapestries saw a decline, replaced by the advent of wallpaper. The Industrial Revolution, accompanied by automated processes like mechanical looms and weaving machines, ushered in an era where plain fabrics could be mass-produced at significantly lower costs. Regrettably, despite these advancements, craftsmen still faced exorbitant expenses when producing intricate patterns. The art of tapestry weaving, once a flourishing craft, became a costly endeavor.

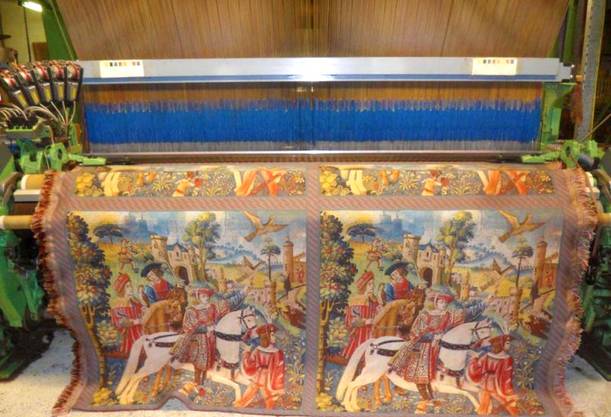

Around 1805, Joseph Marie Jacquard (1752-1834) revolutionized weaving by introducing a more sophisticated loom that utilized "punched cards" to precisely control the position of each thread in the weaving process. Earlier, in the second half of the XVIIIth century, Jacques de Vaucanson had pioneered the creation of the first mechanical looms. Flanders, with its rich tapestry design and weaving expertise, emerged as a pivotal region hosting numerous workshops. Presently, state-of-the-art Jacquard looms, incorporating advanced technology, are employed to craft exquisite Jacquard tapestries, offering enhanced flexibility for the creation of new and intricate designs.

The historical significance of old Flanders finds poignant expression in one of its most renowned exports: Belgian tapestry. The art of tapestry weaving, blending artistic creativity with meticulous craftsmanship, produced treasures now gracing private collections, esteemed museums, and public buildings across the globe. Today, this venerable tradition continues to thrive in the tapestries crafted and distributed by Mille Fleurs Tapestries.